Coronavirus, the Economic Crisis and Indian Capitalism

By Michael Roberts

Below is the transcript of the presentation that I made on 30 April 2020 to the Indian Students Forum (TISS) in Mumbai. It has been published by Students’ Struggle, the monthly bulletin of the Students Federation of India, a student organization associated with the Communist Party of India (Marxist). It is a little out of date on the COVID-19 cases and deaths but I am republishing the presentation to blog readers as I think it still sums up my position on the nature of coronavirus crisis. It is very long. But this is an exception to the rule. It was transcribed for us by Goutham Radhakrishnan, a research scholar at TISS.

Here we are, on the 30th of April, with a recession around the world, where there are now millions of cases of coronavirus which has hit almost all regions, making it a pandemic. We also have an increasing number of deaths, particularly in the United States and Europe. The number of cases is also increasing in other parts of the world—in Latin America, Asia, and to some extent, also in Africa. Clearly, the disease is spreading across the world and it is not over yet. We need to analyze what it means and also how it is impacting the economy.

With this particular virus, the question that is often asked is if it is really like a flu or if it is no worse than a flu. We have the flu every year, at least in the northern hemisphere and also elsewhere, usually in the winter period. Lots of people die from the flu, particularly elderly people and influenza remains, among other diseases, an important contributor to annual deaths in the world. Some people argue that the current coronavirus is much like the flu. The first thing to say is that all of these pathogens, including flu, have become much more prevalent in the last decade or so because of the increasing connection between the human beings into the remote parts of the world including forests, which are home to wildlife, particularly wildlife that has carried many of these pathogens for thousands of years.

Now through the inexorable expansion of human activity—logging, fossil fuel, exploration, urbanization in general—the wildlife species carrying these pathogens have come much closer in contact to human beings. It is spreading through the industrial farming of animals in closed areas, which has led to these pathogens transmitting themselves from the wildlife to industrial–farmed animals into human beings. We know that this particular virus started, it seems, in a wildlife market or at least in an area around the wildlife market in Wuhan in Hubei province in China. This is not just the case of China but elsewhere also with the development of markets. But why are there wildlife markets? Often because poorer people find it difficult to get food from the industrial farming process and they look to other ways to provide them with sufficient food. Wildlife catching has also become a market under capitalism and has become more prevalent, which has led to the risk that these pathogens will spread in human beings as they clearly have done.

And it is not like the flu. We look at the infection rate of COVID-19, its two to three times more infectious that the annual flu. It incubates over a longer period, which is dangerous because it means we don’t know it is happening until it has already hit us, and it has spread around. The hospitalization rate for COVID-19 is much greater than it is for flu, maybe six or seven times more. As far as we can tell, the fatality of infected people on a global scale is coming in after the lockdown at about 1%, maybe a little less. But if the pathogen was to spread to the mass of the population at a 1% mortality rate, at a rate of infection of six to 10 times more than the annual flu, then millions of people are likely to die.

Now, this disease and other pathogens have been brought to the attention of the governments around the world for some time. We can go back several years but the World Health Organisation (WHO) has been warning us of the danger of these pathogens turning into pandemics around the world and infecting human beings. But governments have really ignored this. They have taken the chance that nothing is going to happen, and it is not going to be dangerous and they don’t need to prepare or spend any money on it. Just only in September 2019, the UN Global Preparedness Monitoring Board pointed out that preparation by governments is totally inadequate and a pandemic is coming, and unless they do something about it and get ready, the health systems are going to be overwhelmed and could escalate into a disaster. Well, here we are just a few months later in the middle of such a disaster.

At the same time, it is worth considering that over the last 10 or 15 years when these pathogens have become much more serious and spread on a pandemic basis, nothing is really being done to use resources to find out more about them and to prepare the vaccines that could save us from serious illnesses and diseases around the world. Vaccine is obviously the answer but there is no vaccine for this virus. A universal vaccine for influenza—that is to say, a vaccine that targets the immutable parts of the virus’s surface proteins—has been a possibility for decades, but never deemed profitable enough to be a priority.

Big pharma does little research and development of new antibiotics and antivirals, although this is what benefits public health. Of the 18 largest US pharmaceutical companies, 15 have totally abandoned this field. Heart medicines, addictive tranquillizers and treatments for male impotence are the profit leaders and very little attention is given to defences against hospital infections, emergent diseases and traditional tropical illnesses. Hence, part of the problem has not only been that the governments did not care, but also that research has not been done by the big capitalist pharmaceutical companies around the world because it is not profitable.

Sober-minded epidemiologists suggest that somewhere between 20% to 60% of the world’s adult population could catch this virus. The death rates are very dependent on the level of lockdown, but is certainly coming in at around about 0.5 to 1% of everybody who is infected probably by the time we get to the end of it. While the exact death rate is not yet clear, the evidence so far does show that the disease kills around about 1%, making it ten times more lethal than the annual flu.

That sort of level of cases and hospitalization is overwhelming or likely to overwhelm most healthcare systems in the world as is proved to be the case, because they will have no capacity for dealing with this. No testing, no contact and trace, and no ICU beds sufficient to deal with a huge increase in the number of people becoming ill and needing hospital treatment, particularly old people who can hardly move very much. Since there is no vaccine to combat it, nor any approved therapeutics to slow the course of its toll on the human body, the current situation could continue for some months or even longer ahead.

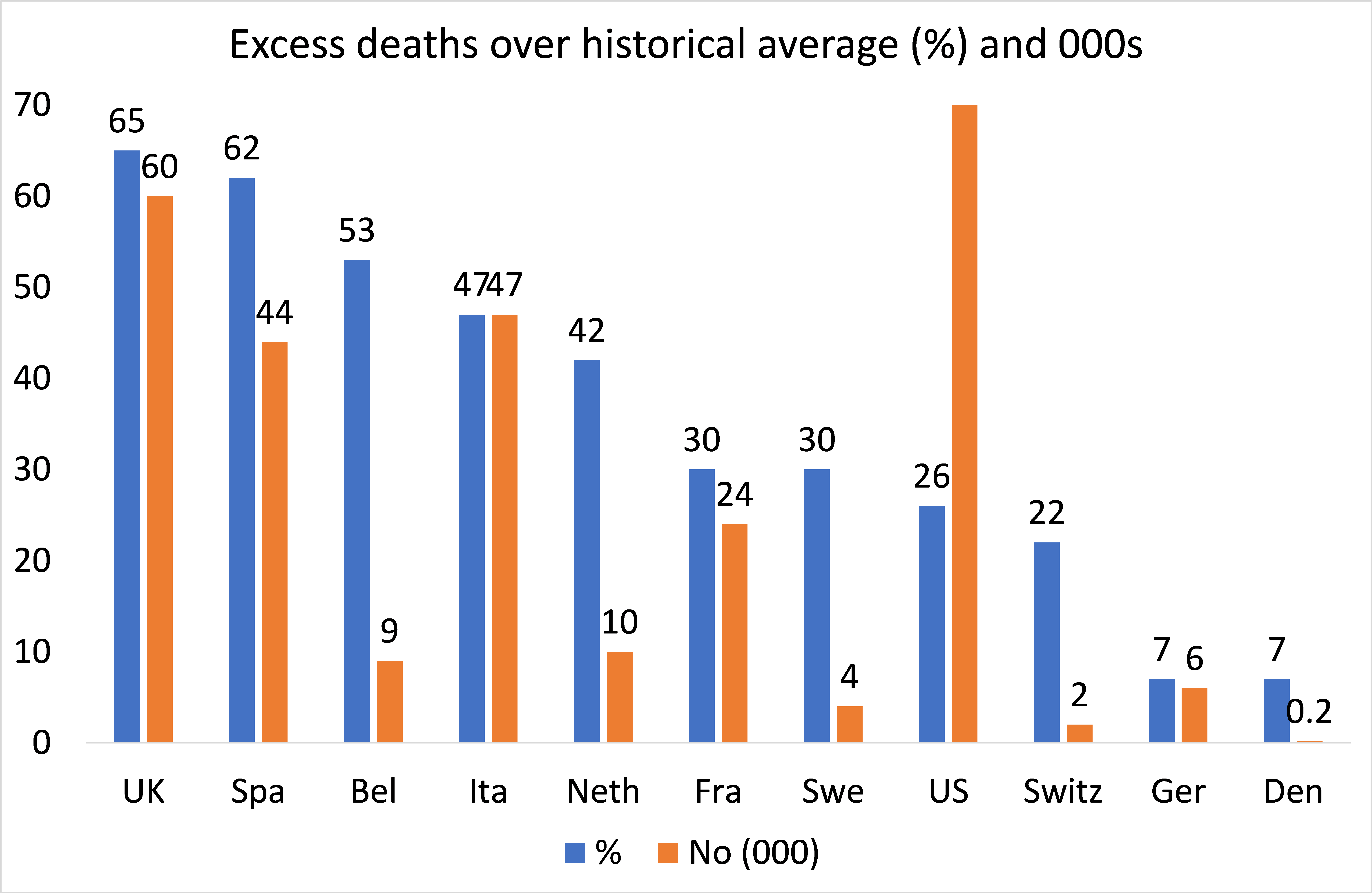

The blue part of this graph is the normal annual mortality rate in various countries. And you can see how many people died in a year per thousand population in these countries. If this pandemic is allowed to spread without any containment, any control or without any protective measures, then the number would more than double in many countries or at least double the amount of people who would die. Depending on how far up the dotted white bit you can go to the top, you could have 35 to 50 million deaths in this pandemic. But of course, that is not what has happened. Health systems and governments everywhere have desperately tried to contain the impact of the pandemic. The little red block (in the graph) shows how successful they have been. If you take the United Kingdom, Spain or Italy, you can see that they have not been that successful and the number of deaths has been way above the normal rates. In fact, figures are now coming out across the board in many parts of the world on how much increase there has been in excess deaths over the normal annual deaths, even with the lockdown and containment policies.

Figure 1 (Source: Financial Times Coronavirus Monitor)

Another argument presented often is that only the old and the sick die from this pandemic. 80% or more deaths are of individuals above 70 years of age and if you are a child up to 9 years of age, there are no deaths. Right up until you get to 50 years or so, the number of deaths is a lot less, even among those hospitalized. The vast majority of people infected would show no symptoms at all and if they do, it is very mild. So, what is all the fuss about, is the argument.

Let us leave aside the question of whether it is right to let the old and the sick die, which within the financial circles I work in, a lot of financial executives and people who advice governments and so on, quietly and privately, seem to agree upon. They argue that if all of the old people and sick people died from the pandemic, we can boost productivity, because these people cost us money and they produce nothing. In some ways it would be better if they were “culled” from the world, so that we have a more productive human population. This is an old theory of Thomas Malthus from the early nineteenth century, that there was no way to improve the lot of the majority of people, because there were too many people and it was better to let plagues and other things “cull” all the unfit and you would have a more productive workforce. And that had to be done progressively.

This disgusting and grotesque theory still has an echo, even now, among people who claim that it does not matter if the old and sick die and we should do little about it and let the young people just be infected. However, that is not a view that is possibly politically acceptable for any government, and moreover health systems would be overwhelmed, disrupting their ability to deal with existing patients and people with other illnesses; and probably causing an increase in such secondary mortality rates (and this time in younger fitter people too), especially in countries more severely affected.

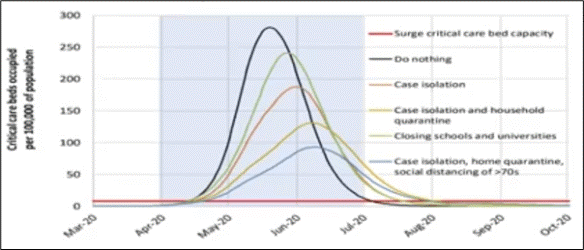

The efforts therefore have been to try and “flatten the curve,” as it is called. In other words, if you look at this graph (Fig. 2) the black line tells that if nothing is done, you are going to have a massive increase in the number of beds that you need compared to the red line at the bottom which is what most countries have got. There is a massive difference.

Fig. 2: Curve Flattening (Source: Stavros Mavroudeas | https://leiccuerj.com/2020/04/04/apandemia-de-coronavirus-e-a-crise-economica-e-da-saude/)

Therefore, you have to contain this in some way otherwise there will be people dying in beds outside hospitals all over the place. Containment can mean anything from social isolation, isolating and quarantining infected people, and shielding the old, going further and start closing schools and universities down, to going all the way down to a total lockdown of all economic and social activity and movement that is represented by the blue line that is the flattened curve. The latter means that the infections are reduced, spread out over a longer period and hospitals can therefore cope and not many people will die. But of course, going all the way into a lockdown is a serious disaster. If a country had full testing facilities and staff to do ‘contact and trace’ and isolation; along with sufficient protective equipment, hospital beds including ICUs, then containment along these lines would work—without significant lockdown of the economy.

Only a very few countries have been able to achieve enough testing. Countries that have done the best have used contact and trace and so on, and have been able to suppress the spread of this infection and reduce the cases. Some of the biggest countries in the world have done the least testing and are at the bottom of the table, as they did not have such testing facilities, and therefore have been unable to operate any testing basis. Also, they have not had the required hospital space because most health systems in the last 30 years have drastically reduced their spending on facilities and staffing in order to save money for governments so that they can spend it on other things such as weaponry or helping capitalists profit. They are not prepared to provide decent healthcare across the board. As a result, there is no spare capacity. Any crisis like this then just becomes overwhelming.

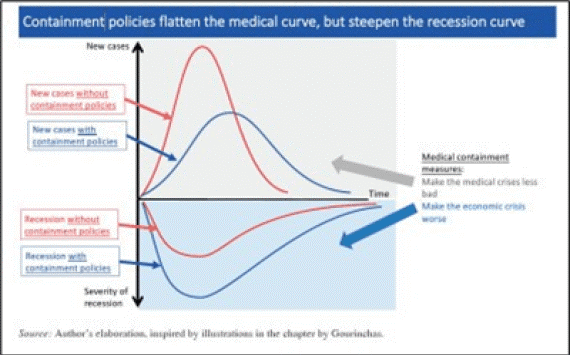

The only solution then is to flatten the curve by a huge lockdown of everything that is moving. This graph (Fig. 3) produced by another Marxist economist in Greece, demonstrates the trade off now between lives and livelihoods as a result of this crisis. The more you flatten the curve on the health front (red to blue on the top part), the more likely you are to widen and increase the negative curve below for the economy (red to blue at the bottom part). The heavier the lockdown to flatten the curve, the more you are going to have a recession and a collapse in the economy.

Fig. 3: Trade-off Between Lives and Economy (Source: https://leiccuerj.com/2020/04/04/apandemia-de-coronavirus-e-a-crise-economica-e-da-saude/)

Lock down and economic slump

We are currently in a lockdown and a slump. We just had figures earlier this week showing the United States down around about 5% in the first quarter and we have not even gone into this quarter, which is going to be much worse. Europe too is down by 3 to 5 % depending on the country and we are going to see even worse figures. 2.7 billion workers are now affected by full or partial lockdown measure, representing around 81% of the world’s 3.3 billion workforce, and they are now facing a massive reduction in their income and employment. Any sort of measure we have had from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation (OECD) and Development, and the private forecasters are projecting anywhere around a 5% reduction in the global GDP this year, which will be way more than the global recession of 2008.

That was called the Great Recession, this will be even greater in its damage to the world economy. Output in most sectors will fall by 25% or more according to OECD, and the lockdown will directly affect sectors amounting up to one third of GDP in the major economies. For each month of lockdown, there will be a loss of 2% in annual GDP growth. This short could exceed any collapse in global output that we have seen in the last 150 years! IMF projects that over 170 countries would experience negative per capita income growth this year.

The OECD June 2020report on the economic prospects for the most developed capitalist economies reckons that “The COVID-19 pandemic is a global health crisis without precedent in living memory. It has triggered the most severe economic recession in nearly a century and is causing enormous damage to people’s health, jobs and well-being.”

In its “Single-hit scenario” where a second COVID-19 wave is avoided, the OECD still reckons global economic activity will fall 6% this year and OECD unemployment will climb to 9.2% from 5.4% in 2019. Five years of income growth is lost across the economy by 2021!

In its double-hit scenario where a second wave of infections hits before year-end, triggering new lockdowns, the OECD forecasts that world economic output will plummet 7.6% this year, before climbing back 2.8% in 2021. And the OECD unemployment rate nearly doubles to 10% with little recovery in jobs by 2021. Even more years of income are lost, permanently.

And alongside the OECD global economic forecast, the World Bank paints an equally pessimistic scenario. In its global outlook, it forecasts a 5.2 percent contraction in global GDP in 2020—the deepest global recession in decades.

Per capita income will contract in the largest fraction of countries globally since 1870!

Advanced economies are projected to shrink 7%. That weakness will spill over to the outlook for emerging market and developing economies, who are forecast to contract by 2.5% as they cope with their own domestic outbreaks of the virus. This would represent the weakest showing by this group of economies in at least 60 years!

“Over the longer horizon, the deep recessions triggered by the pandemic are expected to leave lasting scars through lower investment, an erosion of human capital through lost work and schooling, and fragmentation of global trade and supply linkages.”

This is how severe the situation is.

Of course, the hope is that the collapse will only be short. Just a couple of quarters and then everything will be brought into control and we can recover and go back forward. The stock market in the US is rocketing upwards for two reasons: i) the US Federal Reserve has intervened to inject humongous amounts of credit through buying up bonds and financial instruments so that banks and institutions can keep their heads above water and, ii) they believe that this lockdown will be over soon and then world economy will recover and it will be back to business as usual. We will see whether that turns out to be the case over the next few months. This is in stark contrast with the figures we are seeing about the collapse in the real economy in terms of national output, investment and employment, in all sectors. But the stock market thinks things will soon be fine and they are looking over the drop into the next mountain hoping everything will be up and away again.

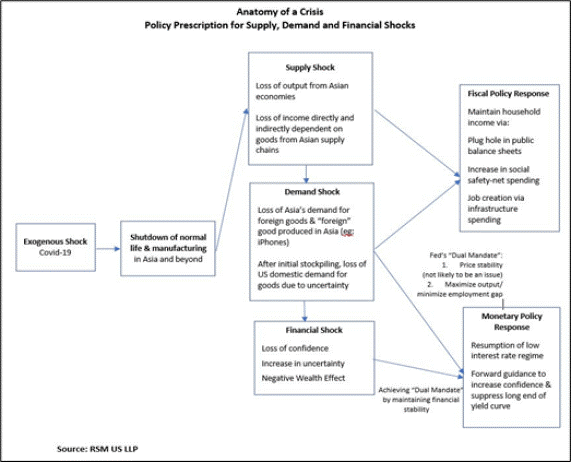

The current situation is one of a huge supply shock. The following figure shows (Fig. 4) that this is not a financial collapse of the banks and the financial institutions like we had in the Great Recession. It starts on the other end, as a supply collapse. We have this so-called exogenous shock. I don’t think it is a shock because we should have predicted these pandemics and done something about it, but it led to a shutdown of normal life and manufacturing. This huge supply shock has now spread to demand because if you are locked down at home, you cannot spend any money or perhaps you haven’t got any money to spend. This demand shock could feed through eventually into a financial collapse with companies that cannot sell going bust and then banks who lend them money also getting into trouble. At the moment the central banks are trying to shore-up that bottom block (on financial shock) in this figure. But they have not been able to do anything about the demand shock or the supply shock which exist.

Fig. 4: Anatomy of a Crisis (Source: RSM, US LLP)

Above all, what this demonstrates, to bring a short quote from Marx, is that what matters in an economy is the workers working. As Marx said: “Every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish” (Marx to Kugelmann, London, July 11, 1868). This is obvious now.

I live in the UK and work in the financial circles and I was trying to ask myself what are the important things that make our economy work and keep us going forward? Who are the workers that matter? Workers that matters are the health workers, the teachers, the drivers, the manufacturing workers, service workers of all sorts, retail shops and so forth. What occupations do not matter? Finance executives, real estate executives, hedge fund managers, advertising executives and marketing executives. When all these people stop work, we would not even notice. But when the workers that matters stop work, we really do notice. It is something worth remembering when you are thinking about who creates the value in our world, in order to provide for the things, we need and the services we require.

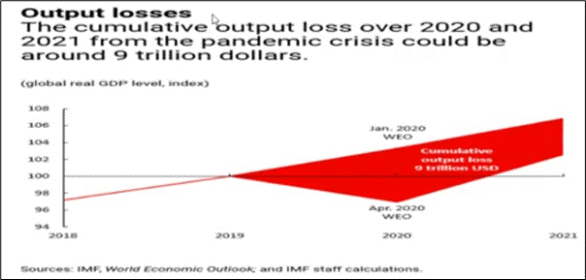

As mentioned, we have this massive lockdown across the world and a huge loss in production in most countries if not all. The red section in the below graph indicates the loss of production that is taking place now. Even if the economy starts recovering in 2021, this loss can never be recovered. Once you have that loss of output, employment and incomes, the gap remains permanently. It is like digging a hole in a ground that you can never fill again. You just have to climb over to the other side and the hole is still there. All those resources are being lost to people around the world particularly the people who needed it the most, the poorest people.

Fig. 5: Output Losses (Source: International Monetary Fund)

In particular, it is the so-called emerging markets that are taking a real tumble. For the first time, since records have begun, the total amount—what is called the emerging markets or developing markets in the world—are going to see a slump, on average across the board. That includes China and India, for the first time. If we take out China and India out of the emerging markets, we get a relatively low growth rate. But now even including them, we are going to have a slump in this year coming through as a result of this collapse in the world economy and lock downs.

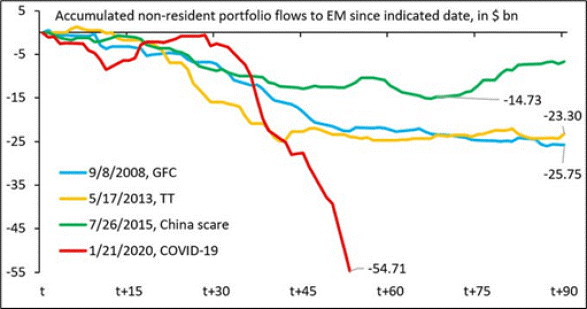

There has been a massive flight of capital away from the poorer countries (Fig. 6) who depend, in the capitalist system, on the inflow of capital from the big companies and financial institutions. The investors have taken all of their money back to where they brought it from and something like a US$ 100 billion have disappeared from the emerging economies. This means they have no credit and facilities in order to expand and it adds to the danger of their own currencies, financial institutions and companies collapsing as a result of flight of the private capital, which is not being replaced by any public capital. The IMF and the World Bank is giving some money, but on the whole, there is no international coordination from the richer countries to help the poor counties in this crisis. They have just been left to fend for themselves and indeed the only way they get some money is by taking out more debt and loans, which could put them in even more difficult problem later on as we shall see.

Fig. 6: Capital Flight (Source: Institute of International Finance)

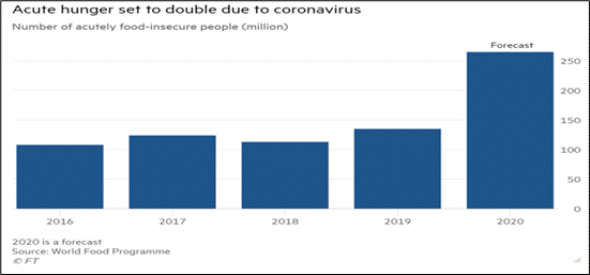

Millions of jobs have disappeared globally according to the International Labour Organisation. The COVID-19 crisis is expected to wipe out 6.7% of working hours globally in the second quarter of 2020 – an equivalent of 195 million full time workers. The labour income loss is around US$ 3.5 trillion (maximum) in 2020. Hence, huge amounts of people are going to be pushed back into poverty. According to Oxfam, under the most serious scenario—a 20% contraction in income—the number of people living in extreme poverty would rise by 434 million to 932 million worldwide. The same scenario would see the number of people living below the US$ 5.50/day threshold rise by 548 million people to nearly 4 billion. Even at more acute level, we are entering a real danger of millions of people just being hungry, starving to death, in a way that should not happen in twenty-first century. It happens anyway as we have seen in years before (Fig. 7), but we are going to see a doubling of the number of people who are basically in a position of starvation over the next year or so.

Fig. 7: Food Crisis (Source: World Food Programme)

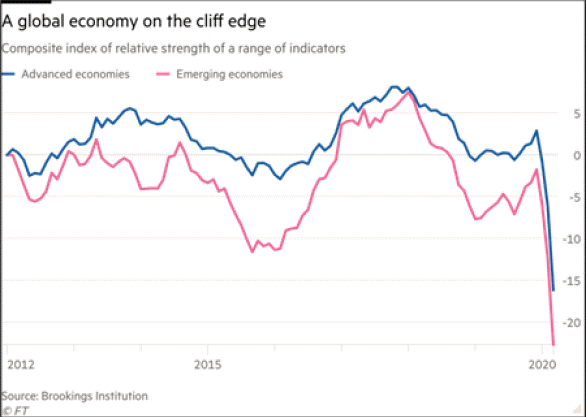

There are some who argue that the lockdown is solely to blame for the economic crisis. But we ought to realize that the capitalist economy on a global scale was not doing very well even before we got to this pandemic. It was on a sharp slowdown. Europe was more or less stagnant, Japan was in recession, many important economies in the global south like Argentina, Mexico, Turkey and South Africa were in a slump already, and even the US was beginning to slow down to a very low rate.

It has been the longest expansion in the history of the US economy since the Great Recession ended in 2009 but it has also been the weakest expansion. Growth has hardly been more than 2% in the US, less in Europe and Japan, and only the emerging economies like India and China has had a reasonable growth rate. Most emerging economies have also had a very poor growth rate compared to the position before 2009. So this has been a very weak growth and it was beginning to come to an end. It was on a cliff edge.

From the graph (Fig. 8), we see that growth was beginning to slow down, both in emerging and advanced economies, and then we had the pandemic and now it has just dived off the edge of that cliff. But it was already reaching there. I want to make that point because some claim that it was all just a bolt out of the blue. It is not, as most economies were getting weaker and they were not ready to deal with this pandemic.

Fig. 8: Global Growth Trend (Source: Brookings Institution)

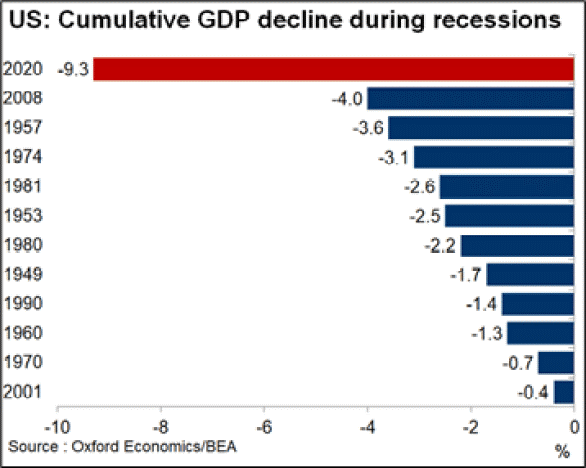

If we take the US, something like a 10% fall in GDP over the next year or so as a result of the pandemic would happen at the minimum. That will be the largest decline since 1930s and way more than anything seen even in the Great Recession of 2008–09 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9: US GDP Decline (Source: Oxford Economics)

Why have most major economies been weak? The answer, in my view, something which I am always trying to bring home to people in my work, is that underneath the movement of outputs and incomes, the key question for a capitalist economy is whether it is profitable to invest and employ people. That is the only reason they produce things. The big motor car companies around the world do not produce cars just because people want them, but they only produce if it makes profit for them to do so. That is the nature of the capitalist economy. They compete with each other to get a bigger share of the market and bigger amount of profit and they use their workforce to try and keep the cost production down as much as possible in order to make a profit, to accumulate that profit, partly to reproduce new things but also to have a good life and be a billionaire.

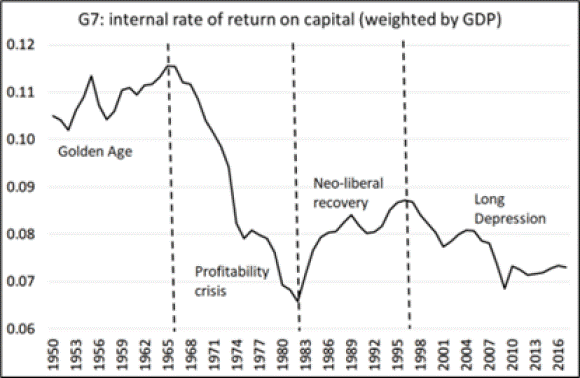

So, profitability is key to capitalism. Below figure (Fig. 10), shows the profitability of major economies over the last 50 to 70 years. You can see that on the whole profitability is really quite low compared to what it was back in the 1960s. There was a big fall followed by some recovery during the last 30 years and workers really had to take a hit for it.

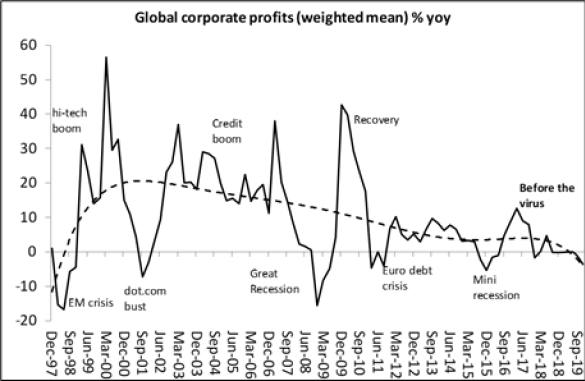

Fig. 10: IRR on Capital (Author’s calculation from Penn World Tables 9.1)

Now profitability was extremely weak as we led up to this crisis, and it suggests that they were in no position to cope with a major collapse in the health systems and economies. In fact, if we look at total global corporate profits (Fig. 11) and not just the amount of profits per investment (i.e. profitability), we see that the total amount of profits had ground to a halt in the major economies as we entered the pandemic. The world economy was already about to enter a slump of some proportion but now of course the pandemic has worsened the slump.

Fig. 11: Trend in Global Corporate Profits (Authors’ calculation from national government sources)

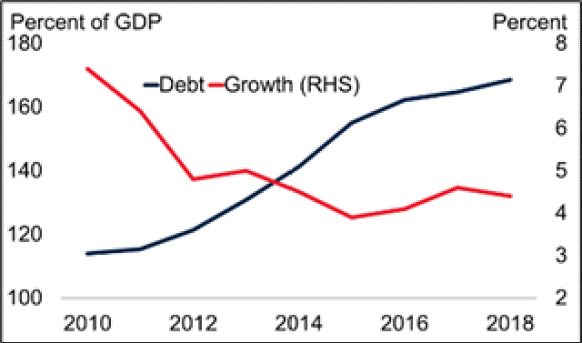

A part of the problem to overcome the low profitability was that the companies were borrowing more, increasing their debt, taking loans from the bank and trying to keep going, particularly the smaller companies that had to take a lot of debt compared to the sales that they were making in order to keep moving. And that has increased the weight of burden on them. If anything should go wrong, they are left with huge amounts of debt. They have to pay and if they default, not only these companies will be in trouble but also the lenders. Emerging markets have seen a dramatic increase in debts while the growth has been slowing down. The point where the two curves intersect in Fig. 12 shows that most emerging economies are in serious trouble as a result of the pandemic.

Fig. 12: Debt versus Growth (Source: https://sbhager.com/covid-19-and-the-coming-corporate-debt-catastrophe/)

Fig. 12: Debt versus Growth (Source: https://sbhager.com/covid-19-and-the-coming-corporate-debt-catastrophe/)

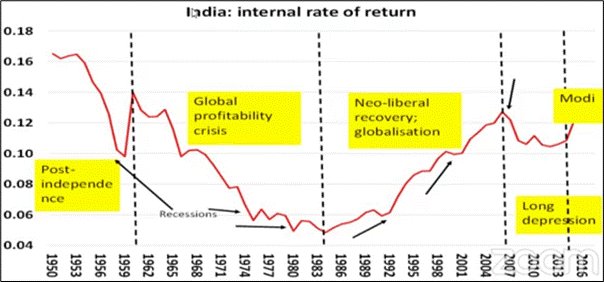

Figures for India (Fig. 13) shows a sharp drop in profitability of Indian capitalist sector post-independence till the early 1980s followed by a recovery through globalization and expansion of neoliberal policies. But also, since the Great Recession, levels of profitability have been generally depressed although in the first couple of years of the Modi administration there was a recovery as they applied measures to try and boost capitalist profitability at the expense of workers. But on the whole, the profitability is nowhere near as it used to be in the 1960s in India.

Fig. 13: Profitability – India (Author’s calculations from Penn World Tables 9.1)

This means that even a country like India, which has been one of the more successful expansive emerging economies, has faced the same difficulties when it comes to profitability. We see that in the dramatic slump in the growth rate from 6 to 7% claimed by the government back in 2016–17—although many argue these figures are not accurate. But now, even in the official figures growth just before the pandemic had dropped quite significantly to 4.7%, a very low figure by Indian standards over the last 10 to 15 years.

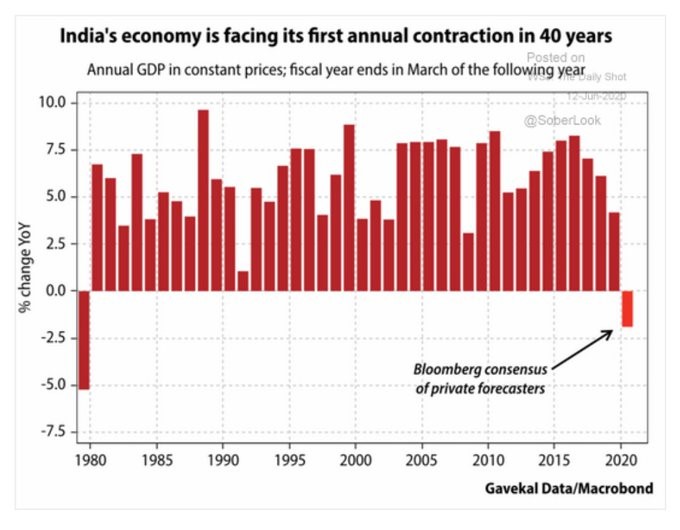

Here is a measure by the IMF (Fig. 14) where they expect India’s growth rate of 4.2% in 2019 to drop to 1.9% this year. I think that is probably optimistic but nevertheless that is a demonstration of how severe the effect of the pandemic, lockdown and the collapse of the global economy is hitting India. Indeed, India could be facing its first annual contraction in GDP for 40 years!

Figure 14: (Source: Gavekal)

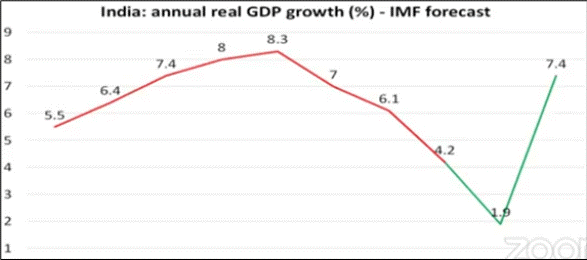

Of course, the IMF expects a recovery in 2021 but one has to wait and watch how it turns out. The green line in the graph shows how much has been already lost in the Indian economy as a result of this crisis.

Fig. 15: India’s GDP Forecast (Source: International Monetary Fund)

Risk for India

The risk for India from COVID-19, according to me, still persists. Yes, it may be less than in other countries but even so, if 65% of the population gets infected without any vaccine or a lockdown, even with a lower death rate (assuming 0.3% similar to Germany) because of the younger population, still two million people could die from this pandemic. Remember, only 0.8% of the population may be above 80 (nearly 75% are below 40), but they still face the real dangers of the pandemic. When people are so poor, it increases the likelihood that they will be infected and suffer severe illness or death from the disease. Many Indians, although young, if they are poor and are unable to have good diets or maintain a healthy distance, then they are also liable to be severely impacted by the virus. The rate of heart diseases in India is almost twice that of Italy and the prevalence of respiratory diseases is one of the highest in the world. India is also home to one-sixth of the total diabetic population in the world, which increases its vulnerability of Indians.

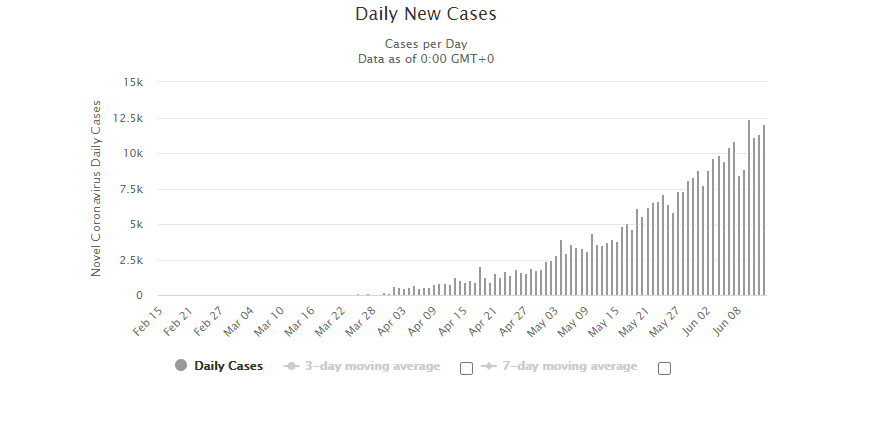

Thus, India is not safe from the pathogen and anyone who says otherwise is not looking at the facts. Latest figures on the daily COVID-19 deaths in India show that it is not really coming down at the moment. There is gradual increase in the number of infections and deaths per day and it is well up from where they were a month ago.

Figure 16: Worldometer Coronavirus by country

There has been no mass testing in India and there are very few respiratory systems (40,000 for a total population of 1.3 billion), isolation beds (1 per 84,000 people), doctors (1 per 11,600 patients) and hospital beds (1 per 1826 people). Therefore, things are not under control in India yet.

India’s and upper-middle-class may be comfortably barricaded inside their capacious homes but the poorest and most vulnerable slum-dwellers who live cheek-by jowl are extremely vulnerable to contracting the infection. Not just the slum-dwellers but also the ordinary working people in Indian cities who have to live and work in small spaces are also at severe risk or catching the virus or losing their jobs. Sky high urban real estate prices mean plenty of working-class families, even those with two earning members, can only afford the tiniest of homes. India is one of the most unequal countries in the world when it comes to wealth.

The top 1% own more than 50% of the India’s personal wealth, and the top 10% hold almost 80%, which is only beaten by countries like Russia and Thailand on this list. India is more unequal in terms of wealth compared to the US, which is the worst of the advanced capitalist countries. The number of people living in slums is over 100 million which is way more compared to other countries in South and Southeast Asia. This population is at risk at all times in this crisis.

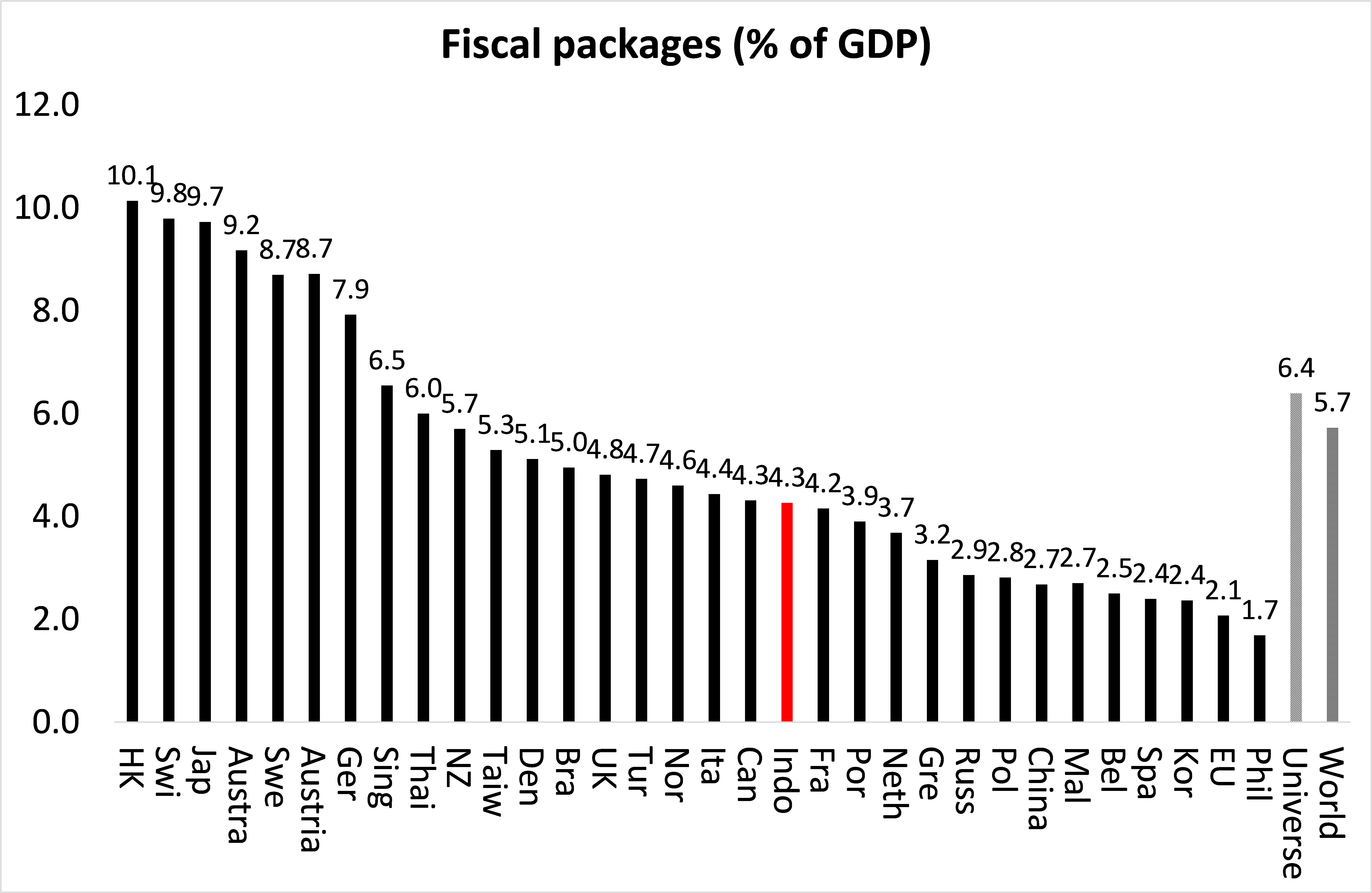

What is the Indian government doing about this crisis? Across the world, country stimulus responses vary from 1% of GDP to 12%. Rich countries seem to have announced larger stimulus packages (5 to 10%) and developing countries have announced smaller packages (2 to 5%).

PM Modi announced a Rs 20 lakh crore stimulus package—close to 10% of the Indian GDP. That sounds large but the bulk of the support is with loan guarantees for businesses. Cash outgoings for Indian households are much smaller. This limited fiscal help is well below the global average.

Fig. 17: Author’s calculations (Source: Michael Roberts)

In effect, the Modi government is spending little on the emergency. It has a combined state and central fiscal deficit hitting 10% of the GDP as against the budgeted 6.5% and is unwilling to borrow any more for emergency funds. That is because there is a huge debt to GDP ratio and at 70%, this is about the highest in its peer group. After this crisis you can expect the government to attempt to squeeze back the increase in debt that has taken place. The government needs to spend more but it is spending less than 1% of GDP currently on the crisis. I would leave this to you whether Kerala is doing better in terms of healthcare because it is what we are hearing in the Western media. According to reports the state is has the best healthcare system in the country and they have kept the mortality rate low and recovery rate high.

What is to be expected?

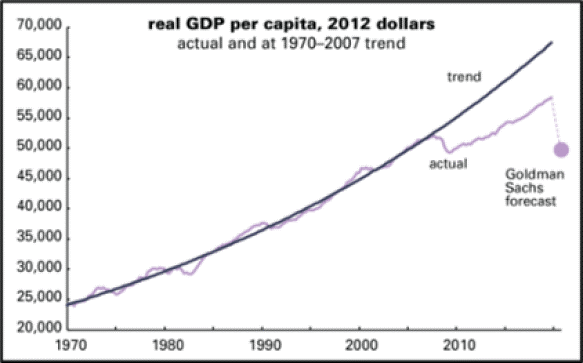

Finally, I would like to discuss what is going to happen. Are we going to return to normal after a few quarters as the stock exchange in the US believes? Here (Fig. 16) is an indication of how far away now the US economy is from its previous trends in the twentieth century. When the Great Recession hit in 2008–09, the real GDP per capita fell and the recovery was much slower than the trend and there is no sign that it returned to trend at all during the period 2010–20.

Fig. 18: US Economy – Historical trend versus current trend (Source: Goldman Sachs)

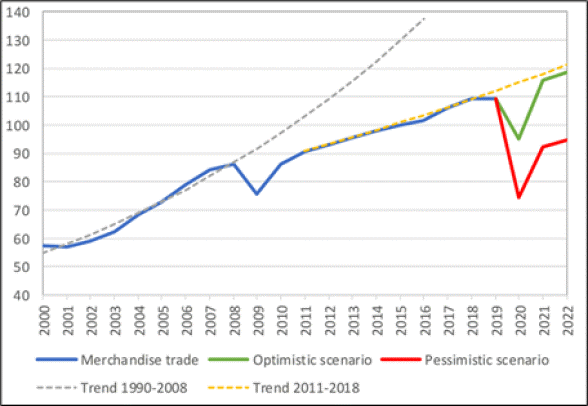

Similar trends were reported by the WTO (Fig. 17), which shows that the trajectory of world trade fell after 2008 and after the slump they set on a new trajectory, which was lower and weaker than the original trajectory. And with this pandemic we are going to slump again and quite likely will have a new, even lower, trajectory of world trade. When we come out of this crisis many economies, particularly those that depend on world trade—manufacturing and, selling commodities and services —would be severely affected and if there is no restoration of the global value chains, there will be no return to normal trajectory and we could remain on this low trajectory forever or at least until the foreseeable future.

Fig. 19: World Trade (Source: World Trade Organization)

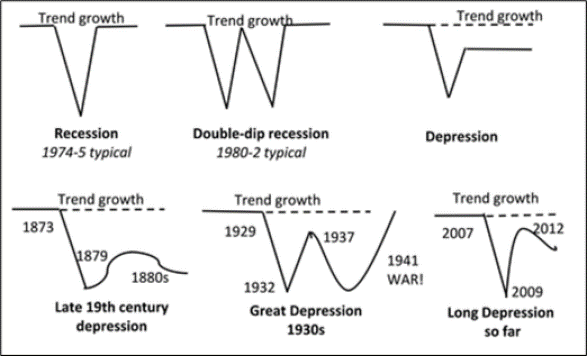

That is why I consider the last 10 years before the virus as a long depression as it was marked by low growth, low productivity and low wages in many countries. It looks as though we are about to enter another leg of this long depression. In the nineteenth century, there was a long depression that lasted for about 20 years from 1870s to the 1890s (Fig. 18). It seems to me that we are about to enter another leg of depression that could last for another 10 years with low productivity, suppressed wages, weak growth, low investment, lack of jobs and training, and low income. The public sector will be under tremendous pressure to be squeezed by capitalism to pave a way out of this pandemic. That is the situation we are likely to enter in the next period.

Fig. 20: A Long Depression (Source: Michael Roberts)

The Lessons

To sum up just a few lessons we have learned.

First, it is capitalism that has generated this crisis and not nature as such. It is a combination of industrial farming, climate change and all the other things that have produced this pandemic.

Second, the market has failed to cope with this pandemic. Everywhere governments based on capitalist markets have failed abysmally, whether it is their pharmaceutical companies or their health systems marked by fund cuts. They have had to interfere in the most emergency and direct ways rather than prepare for this.

Third, COVID-19 has exposed that it is the workers who are most exposed to this infection. It is those workers whose jobs that are most undervalued by this system who we rely on the most, and not the ones making money on the stock market.

Fourth, with the total failure of private healthcare and big pharma, what we need around the world is coordinated free public health system, with mass public investment in research and production of medicines and vaccines, to ensure that these pandemics when they come again can be dealt in a much more efficient way with minimal loss of life.

Fifth, instead of bailouts of big business and banks, which is what the big economies around the world are starting to do, we need to take over these companies and plan them so that they don’t go back to the “normal’ of being driven solely by profitability.

Sixth, it is staggering to me that a company like Amazon, which is now making huge amounts of money, US$ 10,000 a second by delivering things around the vast economies is not publicly owned. This is a company that requires control by democratic decisions of the people. Besides, key services like mail, broadband, and social media should be public operated to meet the need of the people and not just make profits for the few.

Finally, above all, the debts of poor economies should be cancelled and profits from tax havens should be moved out into governments so that profits of big multinational companies can be used to improve and maintain public services.

These are the lessons we can learn from this crisis. This is not going to be an easy period and we are not going to come out of it very quickly. We in the labour movements and working people must recognise the things that we need to do and struggle for, once the lockdowns and the pandemic is over, as capitalism will try to return to business as usual.

Michael Roberts is a Marxist economist based in London and blogs at the nextrecession.wordpress.com